amazon

2005

16mm film, mute

1 minute 34 seconds

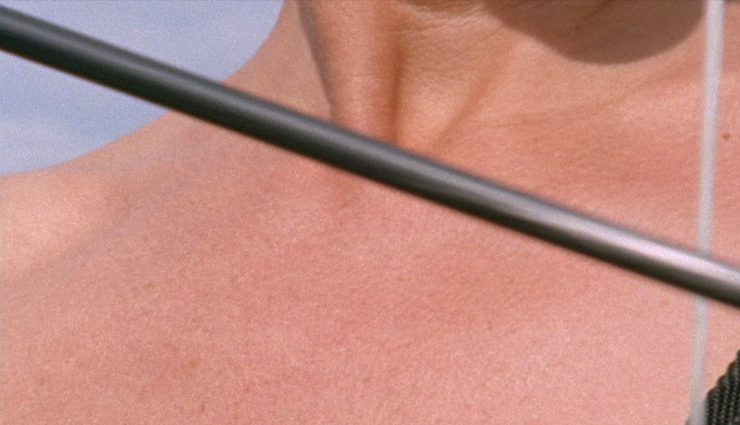

amazon is a 16 mm film projection of an androgynous figure shooting a bow and arrow. A fast edit gives this minute and a half long film the sense of a single shot. For the most part, the camera is tight on the body – neck, chest and arm muscles snap between tension and rest. When it jumps back the camera exposes the torso as that of a single-breasted woman. Under the glare of harsh sunlight the woman relentlessly shoots arrow after arrow, each imprinting stark shadows on her skin. Her target is never visible; what is involved in getting the arrow to it seems more vital than where or what the target might be. amazon makes reference to the Greek myth of a matriarchal society of brave female warriors who are said to have cut off one breast to hit their target better. The work speaks of harnessed strength, female courage and determination. amazon was conceptually edited after the second movement, Allegro Molto, of Shostakovich's String Quartet No.8b In C Minor, Op. 110; a score composed following a visit to Dresden where Shostakovich was confronted with the devastating effects of the bombing of the city during the war. In the end, however, the film is mute.

balance

Mark Ravenhill

The world is in part a thing to be amazed by: to look upon with astonished eyes, to take pleasure in its mysteries and complexities. To trust that it has an ultimate symmetry, a balance that we can never fully comprehend.

Often I feel that sense of amazement: the fascination of watching fire or water or snow falling, their shifting unpredictable patterns. Their aliveness that has no claim to hidden meaning and yet does have a mystery.

The presence of life in a burning tree or the mountain covered with snow seems to have a secret that is a great pleasure but also a great and surprisingly enjoyable fear.

And sometimes I look at other human beings or myself with that same sense of wonderful fascination: the complexities of our beauty and ugliness, the persistence and flux of our being. There is great pleasure to be had in observing this balance.

Balance.

I hear that word spoken and my first instinct is to counter it, resist it with imbalance or unbalance. To destroy balance.

I am surprised to find that this is my spontaneous reaction to hearing the word ‘balance’ spoken. I’m unsettled to find that I feel so strongly that balance is an enemy.

But the world is also a thing to be argued with. To be angered by its fixedness, its relentlessly repeating patterns. And this is the dominant passion that I have, this anger, overwhelming any pleasure that I take in balance.

I suppose here I mean mostly the human world, the cruelty and indifference of our dealings with each other, of the harsh mechanisms of power that we construct.

But also the pain of aging, illness and death. It’s impossible (for me and, I would guess, for you) to experience these things simply with fascination or amazement. These I want to fight, disrupt, unbalance just as much as I want to disrupt the mechanisms of social power. They come from nature, they are natural but I can’t reconcile myself to them. I will fight them.

Nature we are told is made from balance. Look at an isolated moment and we might see cruelty or destruction. But over time and place, nature will always counter and correct and return itself to a state of balance. And this balance, we’re assured, is better, greater and wiser than we are.

But my death is not part of that balance. And I am angry that this wisdom of nature could be greater than mine.

To write these words makes me feel very male.

This is not a pleasant feeling for me. I would like to think of myself as somewhere more neutral on the gender scale. Masculinity is not something I take pride in.

But to challenge nature and death, to want to be greater than them is to be a stereotype of the egotistical, arrogant, individualistic self.

I am Faust with an iPhone and a middle-aged belly. I am ridiculous.I am a child.

The baby creates imbalance, unknowingly at first. It cries, it shits, it falls. Another returns it to balance. The Mother is there to restore the balance.

At some point the child realizes that it has this power. It can deliberately cause a disruption or disturbance and Mother will restore the balance. Perhaps already at this early stage, it is the male child that makes the greatest use of this discovery, is drawn to creating the greater disturbances.

The boy child is performing for the Mother. It gives the boy child a sense of power, but he also believes that it gives the Mother a feeling of pleasure that she is able to complete the performance by restoring balance.

As men, we carry this performance into the world. We arrive in a situation, a scene and we see what is fixed, what has reached a point of stasis and we act to disrupt that, to create an imbalance.

By this we assert our power.

And we offer the possibility of pleasure for those who offer to restore and heal the wound that we have created. The space that we open up for the female is that of the other who will restore balance to the disorder we have created.

For me, this is an essential element of the theatre thatI create. It is a destructive act. I create an opening scene of stability and then introduce an event that will disrupt the balance, introducing more disruptive events until the audience confronts whatever it is that a fixed order of behaviour and belief has concealed. I leave it to the audience to create a balance for themselves after the performance, just as the baby leaves Mummy to clear up the mess.

Something altogether different is happening in A K’s work. It seems to be coming from an impulse far away from my own masculine ego. It seems to be profoundly female and also mature. And its ease with itself makes me feel uncomfortable with my own masculinity and my struggle to mature.

A K’s work does not strive to disrupt. But nor does it simply observe. It makes concrete interventions into the world, acts that exist alongside and inside the natural and the man-made, confident enough of their own existence that they do not feel the need to attack the order into which they have been introduced.

The Amazon terrified her male enemies partly by her sheer height. She was as tall or taller than a man. But most notably with her single breast, the other breast having been chopped off by the Amazon herself. The Amazon had removed the breast so that she could be an effective firer of an arrow. She was an ur-cyborg. But the certainty of being hit by the Amazon’s arrow is less fearsome to the male observer than the asymmetrical woman who has elected to display an unbalanced body.

A K’s Amazonian woman has no enemy. The arrow must logically be red at a target. But here the target is not the completion of the act. The act of pulling and releasing the bow is a finished act in itself.

This woman is not defining herself in relationship with anyone else. She does not want to attack or to heal the other. She exists entirely for herself and for the suspended moment in which she acts.

The camera as an agent of the male gaze has historically often attacked the female body by dismembering it. It isolates the legs or the breasts or the face until the woman is a montage of disconnected body parts. A K’s Amazonian is observed in segments but no dismembering takes place. Each body part exists independently and yet in harmony with the others. A breast has gone but the body is reconciled to this. Balance has been achieved.